15

Jun

Obituary: Franco Zeffirelli

Legendary Italian filmmaker, best known to many as the director of the 1968 adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, has died aged 96.

“He had suffered for a while but he left in a peaceful way,” his son Luciano told the Italian media. Great Maestro has died at home on Saturday morning in Rome, Italy. His adopted sons Pippo (Giuseppe) and Luciano Zeffirelli, as well as his doctor and priest, were beside him till the last moment. Zeffirelli's favourite little white dog Dolly never left Maestro's side either.

Prime Minister of Italy, Giuseppe Conte said he was "profoundly moved by the death of Zeffirelli who was an Italian ambassador of cinema, art, and beauty. A great filmmaker, scriptwriter, stage designer. A great man of culture". Italian Minister of Culture, Alberto Bonisoli called the late Franco Zeffirelli "a genius of our time". The mayor of Rome, Virginia Raggi expressed her condolences on Twitter: "His original point of view and solid manner of storytelling have forever entered the history of Italian and International cinema".

Franco Zeffirelli remained an Anglophile through his lifetime and thus, he proudly accepted an honorary knighthood in November 2004, becoming the first Italian citizen to be so recognized. In a lavish ceremony at the residence of the British ambassador to Italy in Rome, Ambassador Sir Ivor Roberts awarded Franco Zeffirelli on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II. "I feel so English tonight," the prolific director stated as he accepted the blue, gold and silver insignia.

The great Italian earned his KBE for "valuable services rendered to British performing arts", including multiple acclaimed Shakespeare adaptations to film and stage, and 1999's Tea with Mussolini, a film that starred three British dames: Judi Dench, Maggie Smith, and Joan Plowright. "It's the greatest conquest, recognition, I have received in my life, practically", Zeffirelli told the Associated Press right after the ceremony. "I can't believe it".

Some people believe Zeffirelli fully expressed his brilliant talent in his stage works while others give more credit to his outstanding film adaptations of Shakespeare. Still, no one could explain his motivations better than one of the greatest directors of all times himself: “I am not a film director. I am a director who uses different instruments to express his dreams and his stories to make people dream”, Franco Zeffirelli told the Associated Press in a 2006 interview.

Zeffirelli worked with such opera legends as Maria Callas and Tito Gobbi (Maria Callas at Covent Garden, 1964);

Luciano Pavarotti (Don Carlo, 1992);

Plácido Domingo (La traviata, and Pagliacci, both in 1982);

Renato Bruson and Yelena Obraztsova (Cavalleria rusticana, 1982), Katia Ricciarelli (Otello, 1986);

as well as with the movie stars like Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton (The Taming of the Shrew, 1967);

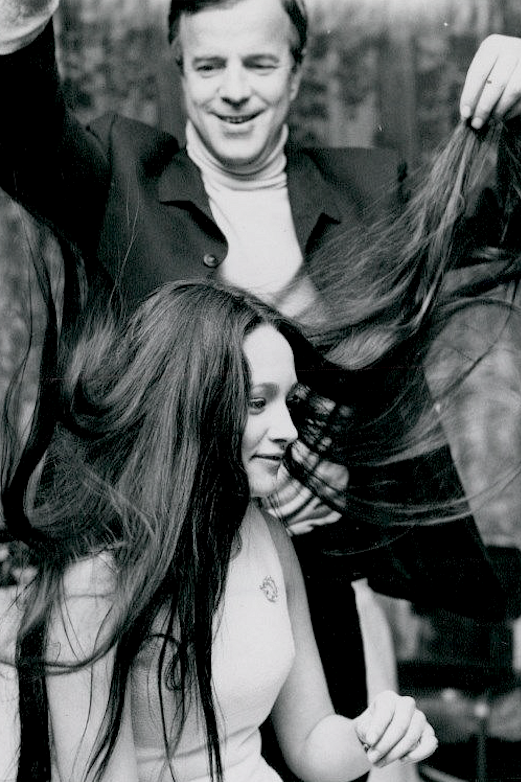

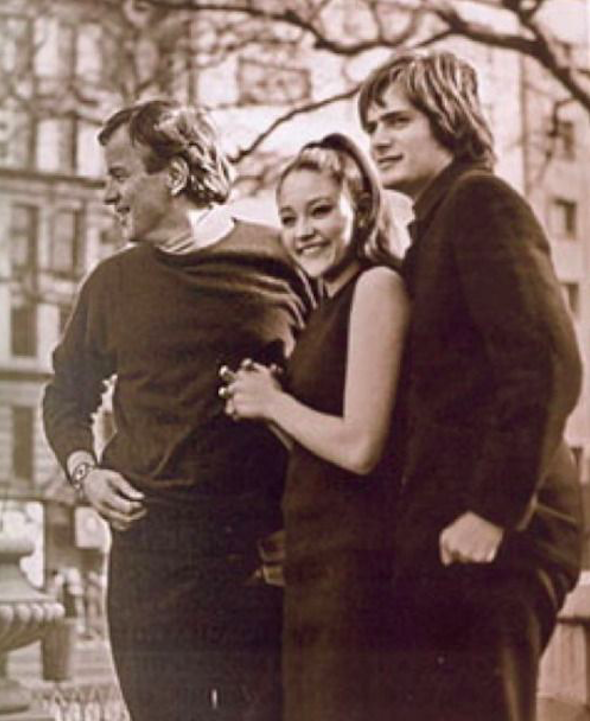

Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting (Romeo and Juliet, 1968);

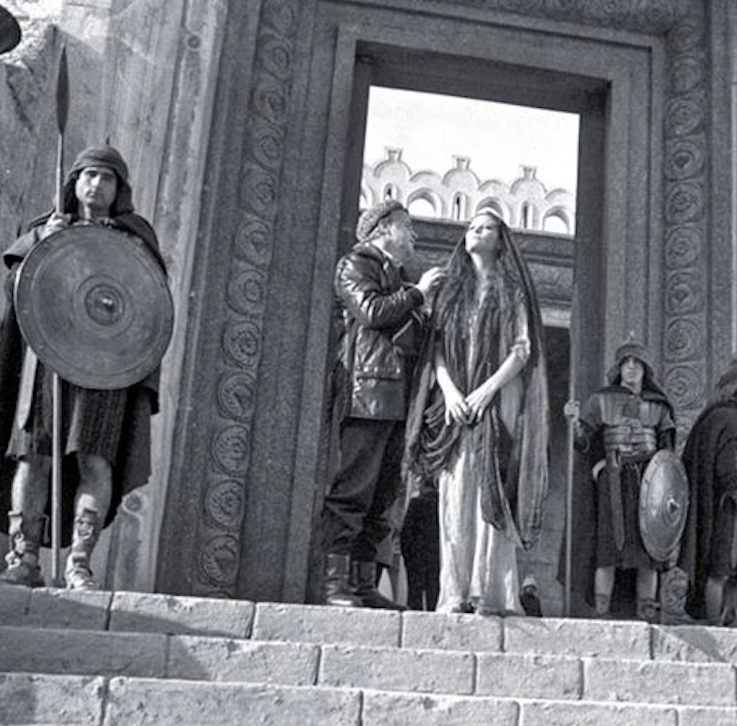

Laurence Olivier, Michael York, Anthony Quinn, and Claudia Cardinale (Jesus of Nazareth, 1977);

Brooke Shields (Endless Love, 1981);

Mel Gibson, Glenn Close, and Alan Bates (Hamlet, 1990);

Charlotte Gainsbourg and Geraldine Chaplin (Jane Eyre, 1996);

Judi Dench (Tea with Mussolini, 1999);

Fanny Ardant and Jeremy Irons (Callas Forever, 2002).

Even in his very first film Camping (1958), Zeffirelli has got Nino Manfredi, one of the most prominent Italian comedy actors of all times, starring.

Franco Zeffirelli directed for stage La Bohème (1965), Much Ado About Nothing (1967), Otello (1976) with Plácido Domingo and Mirella Freni, Carmen (1978) with Plácido Domingo and Yelena Obraztsova, Turandot (1987), Pagliacci (1998), Don Giovanni (2000), Aida (2001), La Bohème (2003), Madama Butterfly (2003) and many other operas.

Apart from the impressive list of masterpieces that the great Italian director has left behind for the next generations to watch and enjoy, Zeffirelli revealed a fascinating story of his birth in his 2006 autobiography.

His mother, Alaide Garosi Cipriani, was pregnant with another man’s child when her lawyer husband died. After his funeral, on 12th February 1923, Alaide gave birth to a son whom she called Gianfranco. Since her lover, Ottorino Corsi, was already married, their child could have neither of his real parents' surnames. Alaide decided to name the boy 'Zeffiretti' ('little breezes'), after Aria for Soprano Zeffiretti lusinghieri ("Pleasant Zephyrus") from her favourite opera Idomeneo (1780) by Mozart. A clerk accidentally misspelled the name as 'Zeffirelli' and the baby boy was officially registered as the first Zeffirelli in the world.

The illegitimate child was sent to live with Ersilia, a kind peasant woman, in a village near Florence. In 1925 Alaide took back her son but Franco kept spending his school holidays with Ersilia. The Florentines refused to have their clothes made by a fallen woman who had a child out of wedlock. The loss of regular customers ruined Alaide's previously prosperous business of dressmaking. In addition to all other troubles, a great economic crisis struck Italy. Eventually, the widowed mother-of-four fell seriously ill.

Franco could never forget the horrific memory of the major quarrel between his parents. He believed that his mother decided to start over in another city when she realised she could never make Ottorino leave his official wife and legitimate daughter to marry her, the mother of his only son. Alaide and little Franco moved to live in Milan where her elder daughter resided.

In 1929, when the boy was 6, his mother died of tuberculosis. For a short while, the boy stayed with his sister and her husband who did not want to take care of the young brother-in-law. The child was sent to an orphanage in Florence where his father's cousins visited him on Sundays. Franco desperately wished the women to take him to live with them. After a few months, his dream came true when one of those ladies, childless aunt Lide, adopted the nephew. She also led a scandalous life, living with a married father-of-two, a naval officer. Aunt Lide and uncle Gustavo welcomed the little boy.

Ottorino visited his son on a weekly basis and this is how Zeffirelli recalled seeing him: "My father always scared me a little. He had more lovers than the hair on his head... When I had to meet him on Saturday afternoons, my aunt would dress me smart. For me, he was a gentleman who used to give me a coin at the end of the visit and leave. I couldn't call him 'dad', nor I knew what to tell him".

Only after his wife died, Ottorino, being forced by his cousins, officially gave the surname to his 19-year-old son. Instead of joy, Franco felt uncertain about such change as he wished to keep the surname created by his late mother. It took some time before he could officially keep both names.

Although Zeffirelli hardly received any parental love from Ottorino, it was Franco's father who arranged English lessons three times a week for the youngster and thus, played a vital role in his future. A young British lady, Mary O’Neill taught Franco to love Shakespeare while his grandfather taught him to love music. Therefore, Zeffirelli developed passions for opera and English culture and literature from a tender age.

During WWII Zeffirelli fought as a partisan until he met British soldiers and became their interpreter. After the war, he went back to the University of Florence with the intention of completing his education. However, he changed his plans after seeing Laurence Olivier's Henry V in 1945 and developing his third passion for theatre.

The architecture student quit university and joined an experimental troupe in his native city of Florence. Soon he was introduced to Luchino Visconti who hired the young man as assistant director for the film La Terra Trema (The Earth Trembles, 1948). Zeffirelli gained additional experience while working along with other film masters such as Vittorio De Sica, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Roberto Rossellini.

In the 1960s, Zeffirelli made his name designing and directing his own plays in London and New York City, pretty soon entering the fame of world cinema.

“I’m 83 and I’ve really been working like mad since I was a kid. I’ve done everything, but I never really feel that I have said everything I have to say,” Zeffirelli told the Associated Press at the dawn of the 21st century. After he turned 90 his health worsed and failed him but the great maestro stayed active anyway. He did not stop making plans and fulfilling his goals until his time actually finished. His son Luciano revealed the last words father told him: "I want to sleep". Rest in peace, Maestro.